What a Garden Can Teach

Bernadette Lambert

(with reflections and artifacts from Sylvia Martinez)Overview

After reading Seedfolks by Paul Fleischman, I realize that an idea as unpretentious as planting a garden can inspire an idea as significant as creating a community. I also believe the concept need not be limited to a fictional neighborhood. I imagine a variety of communities can be transformed through the creation, observation, and preservation of a garden. I know it’s conceivable and possibly threatening. The challenge is how to convince members of a community that it is essential and most likely rewarding.

Then I read “What the Prairie Teaches Us,” by Paul Grunchow. He writes, “The prairie, although plain, inspires awe. It teaches us that grandeur can be wide as tall.” Eureka! That’s it. Why can’t a garden teach us the same lessons learned from the prairie? Are urban students oblivious to what can be “reaped” by planting a seed and watching it grow? More importantly, can a garden teach people how to be a productive and loving community?

In connecting the two texts above, I am suggesting that strong community can be established and perhaps maintained for an extended period of time by engaging participants in real and metaphorical gardening experiences. First, a community must consider what a garden can teach them. That is the essence of the assignment that follows. To augment the discoveries from the lesson, a new community can cultivate a real garden with their choice of a common crop. A garden is defined as a plot of land used for growing flowers, vegetables, or fruit, but I imagine the definition could be expanded to include rocks, butterflies, even photographs or words. If what is harvested is nurtured by the community members, the lesson taught should be the same, and positive change should be promoted within and around the community.

Instructional sequence

1. Read Seedfolks by Paul Fleischman or another short story or novel in which community building is a strong theme.

2. Facilitate a discussion of the found poem adapted from Paul Grunchow’s “What the Prairie Teaches Us,” as students explain the qualities of a garden. For example, ask students to suggest examples of how a garden is patient or tolerant.

3. Using the found poem (where students compose a poem using only words and phrases from the text of Seedfolks), have students work in small groups to create an illustrated poem with images suggested from the text to represent each stanza of the poem. For example, to illustrate how “a garden grows richer as it ages,” students might illustrate the scene when Gonzalo finds Uncle Tio in the garden and realizes “he’d changed from a baby back into a man.”

4. Use the same poem as text for a blank quilt displayed in a common area. The teacher writes each line of the poem on one sheet of paper. Each sheet of paper becomes one square in the blank quilt. Students, in small groups or individually, then draw images to illustrate each square and the quilt becomes a communal text applying the meaning of the poem specifically to the classroom community. For example, students might illustrate the tolerance of their classroom community when a new student arrives and is treated with respect. This step of the activity could take as little as a week or as long as a school year, depending on how long it takes the lesson to be learned. (Remember the garden is patient.) It works well in conjunction with the cultivation of a real garden, as students return to the original found poem, the original text, and make the connections.

Necessary handouts

“What a Garden Can Teach Us”adapted from “What the Prairie Teaches Us” by Paul Grunchow

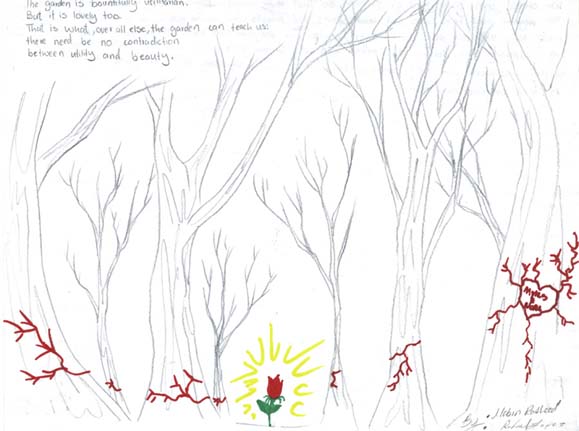

Young garden plants put down deep roots first;only when these have been establisheddo the plants invest much energy in growth above ground.A garden can teach usthat the work that matters doesn’t always show.Diversity makes the garden resilient.The garden can teach us to seeour own living arrangements as stingyand to understand that his miserliness is whyThey so frequently fall short of our expectations.The garden is a community.It is a dynamic alliance of organisms depending upon each other.When too few remain, the community loses its vitality and all perish together.The garden can teach usthat our strength is in our neighbors.The garden is patient.The garden can teach usto save our energies for the opportune moment.The garden grows richer as it ages.The garden can teach usto be competitive without being destructive.The garden is tolerant.The garden can teach usto see the virtue of ideas not our own and the possibilities that new-comers bring.The garden turns adversity to advantage.The garden can teach usto consider the uses that may be made of our setbacks.The garden is bountifully utilitarian.But it is lovely too.That is what, over all else, the garden can teach us:there need be no contradictionbetween utility and beauty.

Student artifact

Editor’s Note: Bernadette Lambert delivered the first version of this lesson to her KCAC colleagues at the second KCAC summer institute. Sylvia Martinez, one of the summer institute fellows, adapted Bernadette’s original lesson for her high school students at Campbell High School in Smyrna. Below are Sylvia’s reflection and her students’ artifacts.

Proposed community interventions: We should

start some kind of program so that kids would stay

out of trouble. The program could have clubs and

team sports. And parents can hang out with their

friends while their kids play with their friends.

The program can have all kinds of clubs like a drawing

club, drama club, music and etc. In the club people

can help each other with class work. And they can

help each other with studying. But the best thing

is that anyone can join.

-- Mobin Rasheed, Rafael Lopez

Teacher reflection

Sometimes having students illustrate invokes that look of fear in their eyes when they imagine their stick figures and scraggly lines appearing on the bulletin board. Despite the normal response, my students were quite excited to illustrate a portion of the poem. They were also asked to choose a character from Seedfolks that best represented the portion of the poem they illustrated. Finally, I asked them to brainstorm ways that they might intervene in their community in a manner similar to the way the characters shaped their community in Seedfolks. Seeing them work in groups on their illustrations changed my mind about creating visual art in my classroom. When students understand something and connect to it, they are able to imagine vividly. After reading Seedfolks and the poem, my students believed in the idea of community and were ready to share their picture of community with the rest of the class.

Sylvia Martinez

Cross-curricular adaptation and integration

Language arts

¨ Keep a journal of classroom experiences that are connected to lessons learned from a garden.

¨ Write a story in which a garden setting has a significant impact on the main characters.

Science

¨ Before planting a garden, classify seeds that are used according to size, texture, shape, etc.

¨ Make predictions about how each plant will grow.

¨ List favorable and threatening conditions for your garden. Keep a journal to post observations of the garden.

Social Studies

¨ Identify famous gardens around the world. Are some gardens considered museums?

¨ Research and discuss how gardens have changed over time.

Psychology/Life skills

¨ Gardening is often described as a relaxing activity. Explain how this could be so.

Mathematics

¨ Plan and outline a garden, preferably a real one, on a scaled drawing.

¨ Chart the progress of your garden by plotting the correlation of growth measurements to time.

Art

¨ Illustrate the garden described in Seedfolks at its different stages of development.

Drama

¨ Hold a mock city council meeting in which the Seedfolks deal with the issue of losing public control of the garden.

Suggestions on how you might adapt this lesson for a different classroom setting

► Just because a text’s primary audience is juvenile doesn’t mean that the text can’t speak to older students and provide a valuable launching point for deep thinking. Sylvia Martinez took Seedfolks into her high school classroom, much like Patsy Hamby took When Clay Sings (see page 67) and Ed Hullender took My Place (see page 142) into theirs. All of these books are written for elementary or middle school audiences, but deconstructing them and doing the research necessary to emulate them using local materials has been a very valuable approach undertaken by KCAC teachers and their students.

-- Dave Winter

Bibliography

Fleischman, Paul. Seedfolks. New York: Joanna Cotler Books, 1997.

Grunchow, Paul. “What a Garden Can Teach Us.” Grass Roots: The Universe of Home. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 1995: 77-80.

© 2000-2001KCAC

No materials on this website should be copied or distributed

(except for classroom use) without written permissions from KCAC.

Questions? Comments? Contact KSU webmaster

Jim Cope.