Creating a New Context for Studying

African Americans' Post-Civil War Education

by Sarah Robbins

In one of the lyrics from her "Chloe" cycle of poems written after the Civil War, African American author Frances E. W. Harper had the sequence's central character describe the shared power freed slaves were achieving through literacy acquisition in the black community. Harper's Chloe character, the heroine of the cycle, declared that:

"Our masters always tried to hide/Book learning from our eyes."

Chloe says whites tried to limit black literacy acquisition because they well understood that

"Knowledge didn't agree with slavery-'Twould make us all too wise."

Harper's Chloe character stresses that, even during the darkest days of slavery, some blacks had been able to "to steal" literacy "by hook or crook." Still, the climax of this poem celebrating "Learning to Read" emphasized the special community benefits that became available to former slaves in the post-Civil War era, when their masters could no longer legally bar them from education. In that vein, Chloe explains that she had "longed to read [her] Bible," and that she therefore worked hard to teach herself, even though some "Folks just shook their heads" at someone "rising sixty" trying to learn to read. Ignoring this reaction, Chloe "got a pair of glasses" and went "straight to work," studying until she "could read/ The hymns and Testament."

Now that she can read, Chloe says, she feels like "queen upon her throne." Furthermore, she links her personal acquisition of literacy to socioeconomic advancement for her people. And she highlights the ability of former slaves to manage their own uplift (Harper, 205-06).

Historians like Jacqueline Jones and James D. Anderson have stressed that the primary force behind educational uplift for blacks after the Civil War came from the African American community and not from Yankee benevolence. Nonetheless, a persistent mythology lingers about the schooling of former slaves in the south from 1865 through the dawn of the twentieth century. This familiar narrative tends to focus exclusively on the enlightened white teachers who journeyed south under the auspices of the American Missionary Association or the Freedmen's Aid Society to establish schools for the freedmen and their children. Indeed, many idealistic New England white women did become teachers of southern freedmen, and often through very charitable motives.

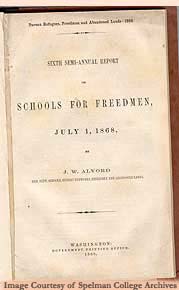

Part of the reason histories of post-Civil War blacks' education have emphasized whites' contributions is that the northern organizations left extensive written records of their work, including handwritten correspondence and log books but also official print publications like the Freedmen's Record. Along those lines, one source of this narrative about white benevolence for blacks was the stories sent home by some of the missionary women, such as Sarah Jane Foster of Maine, who wrote accounts of her work home to be published in her hometown newspaper. Another was the reports of white male administrators of organizations like the Freedmen's Bureau, which printed official documents like the bureau's regular government reports.

Still another was the large number of magazine essays describing these education programs to ensure the support of northern liberals. (This campaign was needed to counter opposition among members of the southern planter class, who had a vested interest in constraining the learning opportunities of their former slaves.) These publications did fulfill an important purpose for their original audiences by generating financial and political backing from northern whites for the education of blacks in the south. But such narratives also contributed to misconceptions about southern blacks.

For example, John De Forest, one of the Freedmen's Bureau officials stationed in South Carolina, wrote a series of articles for the Atlantic Monthly that described the Bureau's essential work. But De Forest's writing also circulated negative stereotypes claiming that blacks were incapable of controlling their own schools and other social institutions-that they were totally dependent on white leadership from the north. While such publications did help champion social programs assisting the former slaves, in other words, they also contributed to misconceptions among many northerners about the (supposedly limited) abilities of blacks to manage their own lives. Thus, the stereotypes also promoted a view of freed blacks as unprepared to participate fully in the nation's political system.

In contrast to these stories published for white audiences, Anderson and Jones have documented ways in which "black educational leaders were critical of popular misconceptions, which attributed the schooling of ex-slaves to Yankee benevolence" (Anderson, 11). For instance, citing the Loyal Georgian, Anderson explains how black leaders consistently expressed support for the Yankee schoolmarms who had come south but at the same time insisted

that these missionaries needed to get over "any vain reliance on their [supposedly] superior gifts . . . [of] intelligence or benevolence. . . ." (12).

One reason alternative narratives of educational progress have been less well known than the version highlighting Yankee benevolence is that many of the publications blacks created about their own community education programs were aimed primarily at an African American readers. Frances Harper herself, for instance, wrote two serialized novels celebrating blacks' managing the educational initiatives in their own communities (Minnie's Sacrifice and Trial and Triumph). But those stories were published originally in the Christian Recorder, a periodical targeted specifically at a black audience. Harper's serialized novels were not available at all until very recently. Thankfully, persistent research by Frances Smith Foster uncovered enough copies of the Recorder to piece together most of Harper's stories for all Americans to read today.

More work remains to be done, however. For example, many of the narratives blacks crafted about their experiences with educational uplift were never published in print form. Passed down through generations as oral family history, many of these stories can still be recovered, as Deborah Mitchell's account here will show. Such stories can help us understand how blacks often led their own schooling and how they sometimes collaborated as full partners with whites to create new institutions such as Spelman and Morehouse in Atlanta. In addition, scholars and teachers need to follow Frances Smith Foster's lead by researching and circulating more material from the black periodical press of the nineteenth century.

By creating a record based on oral histories and a review of little-read publications originally created for relatively small, mainly African American audiences, our "Educating for Citizenship" research team hopes to help refine the historical narrative about post-Civil War educational uplift in northwest Georgia. With that goal in mind, we have focused our specific research on the early days at Spelman College (then a seminary) in Atlanta, Georgia. We have drawn upon oral family histories and limited-run publications like the Spelman Messenger to highlight details about how one group of New England "schoolmarms" and local black leaders collaborated to build an educational institution preparing black women for community leadership.

Showing how the partnership between the Packard-Giles team of New England lady missionaries and local black leaders succeeded in its educational mission can help remedy some lingering misconceptions about the ability of southern blacks to lead their own uplift. At the same time, sharing this story of collaboration across racial lines can suggest some strategies to use in community-based education for active citizenship in our own day. For instance, we believe the history of partnerships involved in Spelman's early history has important implications for linking today's local immigrant groups with the public schools-and, more generally, for teaching programs that empower learners to be leaders in their own communities.

Click Here for additional notes on the development of this material

A Timeline of Spelman College's Early History

by Ed Hullender

Father Quarles and Aunt Ruth: Leaders for Spelman and All of Georgia

by Deborah Mitchell

Early Graduates: Writers and Community Leaders

Transcriptions from the Spelman Messenger

Reflections on Writing (from) an Oral History

by Deborah Mitchell

Doing Archival Research

by Ed Hullender

Bibliography

by the "Educating for Citizenship" Team

Content Design/Management: Traci Blanchard and Marty Lamers

Home | Curricular

Program | Thematic Content

Classroom Resources

| Community Projects |

Who We Are

© 2000-2001KCAC

No materials on this website should be copied or distributed

(except for classroom use) without written permissions from KCAC.

Questions? Comments? Contact KSU webmaster

Jim Cope.